The “No Pain, No Gain” Myth in First Aid

We have all been there. As a child, you scraped your knee on the playground asphalt. You hobbled home, tears streaming down your face, only to face the dreaded brown bottle of hydrogen peroxide or the sharp scent of rubbing alcohol. Your parents likely told you, “It stings because it’s killing the germs,” or “If it hurts, that means it’s working.” This belief—that pain is a necessary indicator of efficacy—is deeply ingrained in our cultural approach to first aid. However, it is important to realize that a stinging wound does not necessarily indicate effective treatment.

However, medical science has evolved significantly since those days. We now understand that the stinging sensation is not a badge of honor or a sign of superior sterilization; rather, it is often a signal of cellular distress. While the intention behind using harsh antiseptics is to prevent infection, the reality is that “the sting” often indicates that you are damaging the very tissues trying to heal you. It is time to update our first aid kits and our understanding of wound physiology, particularly in relation to how we treat a stinging wound.

The Physiological Reaction: Why Do Antiseptics Sting?

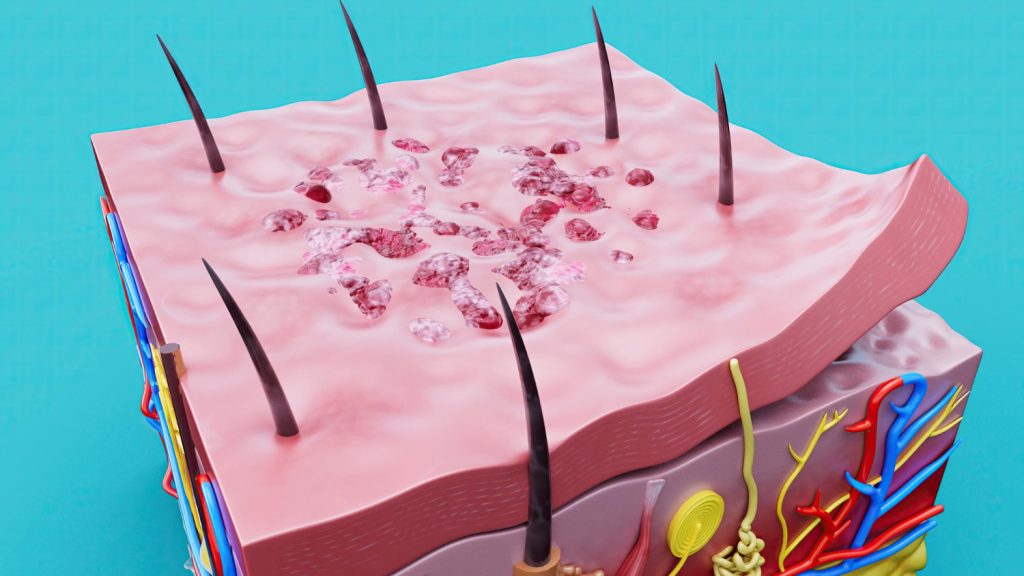

To understand why the sting is unnecessary, we must first understand what causes it. When you have an open wound, the protective layer of the skin (the epidermis) is broken, exposing the sensitive nerve endings in the dermis below.

When harsh chemical agents like alcohol or hydrogen peroxide touch these raw nerve endings, they lower the threshold of heat receptors, specifically the TRPV1 receptors (vanilloid receptors). Essentially, these chemicals chemically burn the exposed tissue, triggering a pain response similar to touching a hot surface. This is your body’s way of shouting a warning, not a confirmation that sterilization is taking place. The pain is a biological alarm signaling chemical trauma to the nerves.

The Usual Suspects: Understanding Common Household Antiseptics

If you open the average medicine cabinet, you will likely find two main culprits responsible for the stinging sensation: hydrogen peroxide and isopropyl (rubbing) alcohol. While these serve excellent purposes for disinfecting hard surfaces, their application on living tissue is highly problematic.

Hydrogen Peroxide: The Bubbling Deceiver

There is something undeniably satisfying about watching hydrogen peroxide bubble on a cut. We have been conditioned to believe that this effervescence represents bacteria dying in real-time. In reality, that bubbling is an enzymatic reaction. Your blood and cells contain an enzyme called catalase. When catalase comes into contact with hydrogen peroxide, it breaks the peroxide down into water and oxygen gas—hence the bubbles.

While this reaction does kill bacteria, it is indiscriminate. It blasts apart the cell walls of bacteria, but it does the exact same thing to your healthy skin cells.

Rubbing Alcohol: The Drying Agent

Rubbing alcohol is a potent disinfectant because it denatures proteins, effectively dissolving the machinery of bacteria. However, when applied to a wound, it acts as a desiccant. It rapidly strips oils and moisture from the wound bed. A dry wound heals significantly slower than a moist one, and the chemical burn caused by alcohol can cause necrosis (death) of the skin edges, leading to a wider wound that takes longer to close.

The Hidden Damage: Why “The Sting” is Counterproductive

The core reason you should avoid stinging antiseptics lies in how your body repairs itself. Healing is a complex orchestration of cellular movements, and harsh chemicals throw a wrench into the gears.

Understanding Cytotoxicity

In medical terms, products that damage cells are “cytotoxic.” Hydrogen peroxide and rubbing alcohol are cytotoxic to human cells at the concentrations usually found in first aid kits.

How Harsh Chemicals Destroy Fibroblasts

The heroes of wound healing are cells called fibroblasts. These cells migrate to the injury site to manufacture collagen, which acts as the scaffolding for new skin. When you apply a stinging antiseptic, you are effectively carpet-bombing the wound bed. You might kill the bacteria, but you also kill the leukocytes (white blood cells) and fibroblasts. Without healthy fibroblasts, the reconstruction of the skin is halted until the body can recruit new cells to the area.

The Risk of Increased Scarring

Because cytotoxic agents delay the healing process and cause inflammation at the cellular level, the body often overcompensates during the repair phase. This prolonged inflammation and delayed closure time significantly increase the likelihood of prominent scarring. If you want a wound to heal invisibly, avoiding the sting is your first step.

Distinguishing Between Cleaning and Irritating

It is vital to distinguish between a wound that is clean and a wound that is irritated. A clean wound has been rinsed of debris and bacteria. An irritated wound has been chemically assaulted.

The goal of first aid is to reduce the bacterial load to a level where the immune system can handle the rest, not to sterilize the skin to the point of sterility found in an operating room. The human body is incredibly resilient; it does not require scorched-earth tactics to fight off common bacteria. Mechanical cleaning (the physical force of water washing away dirt) is vastly superior to chemical cleaning for minor injuries.

Signs of Infection vs. Signs of Healing

One fear that keeps people reaching for the alcohol bottle is the fear of infection. However, mistaking the normal inflammatory phase of healing for infection can lead to overtreatment.

What Normal Healing Looks Like

For the first few days, a wound may be slightly pink, tender to the touch, and perhaps a little swollen. This is the inflammatory phase, where your immune system is rushing to the scene. This is normal and healthy.

Red Flags Requiring Medical Attention

If you are avoiding harsh antiseptics, how do you know if an infection is setting in? Watch for these signs:

Expanding Redness: If the pink area around the wound starts spreading like a streak or a sunburst.

Purulent Drainage: Thick, yellow, or green pus (distinct from the clear yellow serum that sometimes leaks from a clean wound).

Increased Heat: The skin feels significantly hotter than the surrounding area.

Fever: Systemic signs that the body is fighting a battle it is losing.

Modern Wound Care: Best Practices for Faster Healing

So, if we toss out the stinging liquids, what should we do instead? The modern standard of care is focused on maintaining a physiological environment that promotes cell migration.

The Importance of Saline and Water

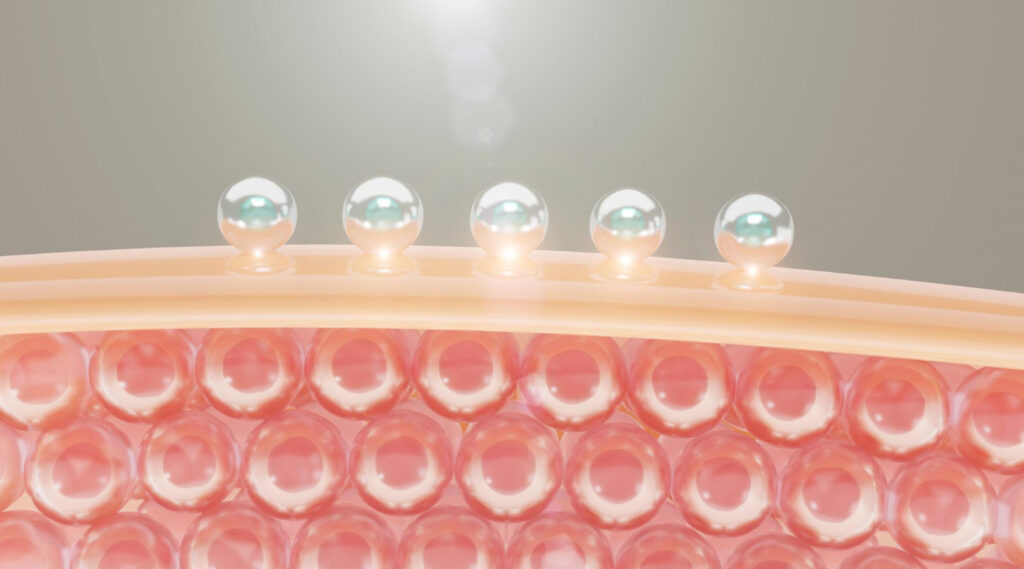

The best solution for cleaning a wound is likely already in your kitchen tap. Cool, running tap water is highly effective at flushing out debris and bacteria. If you want to be more precise, sterile saline solution (0.9% sodium chloride) is the gold standard because it matches the salinity of your own blood cells. It cleans without causing swelling or shrinking of the cells. It does not sting, and it does not damage tissue.

The “Let It Breathe” Fallacy

Another myth that goes hand-in-hand with the stinging antiseptic is the idea that you should let a wound “breathe” and form a hard scab. Modern research shows that a moist wound heals up to 50% faster than a dry one.

When a hard scab forms, new skin cells have to burrow underneath it to close the gap, which takes time and energy. By applying a layer of petroleum jelly or antibiotic ointment and covering the wound with a bandage, you create a moist environment. In this environment, new cells can slide across the wound bed effortlessly, closing the gap quickly and with less scarring.

Conclusion: Embracing Gentle Care

The era of gritting your teeth through the pain of wound cleaning should be over. The stinging sensation you were taught to associate with healing is, in reality, a sign of cellular damage that delays recovery and increases scarring. By swapping out hydrogen peroxide and rubbing alcohol for gentle soap, water, and moisture-retentive bandages, you work with your body’s natural healing processes rather than against them.

Next time you or a loved one sustains a minor injury, remember: gentle is better. Skip the sting, keep it clean, keep it moist, and let your amazing biology do the rest.